A review of the state of foster care in England has just been published. Whilst the report tries very hard to paint a rosy picture of the fostering sector, the data remains virtually unchanged since experts began analysing the way children fare inside the system. The recommendations look mostly at financial issues for foster carers, their status and the suggestion that Independent Reviewing Officers may be dispensable, in a bid to place more funds on the front line.

It’s really all about the money, with a nod here and there to the traumatised and vulnerable children who seem to be cheated out of just about everything.

That the core data about the fostering sector remains almost completely unchanged, or shows no signs of significant improvement in outcomes for children, makes the rhetoric inside the report largely irrelevant. Much of the report’s contents have been noted in previous reports and research documents. Our greatest concern stemmed from the way emotional warmth and affection continues to be blocked or treated like a taboo. This excerpt from the report is hugely worrying:

“All too often we found that foster carers believed that demonstrations of physical affection were frowned upon, or they had been taught to be fearful of potential allegations. In one example, we heard of a foster carer in a room with other carers and changing a baby’s nappy. On completion, she raised the child’s Babygro and blew a raspberry on his bare tummy. Other foster carers in the room were very concerned that her expression of affection for the baby was inappropriate and could even be seen as a safeguarding issue. These concerns and anxieties can result in some children in care not receiving the physical or emotional affection they need that helps them to thrive.”

The report touches upon contact with siblings and birth parents, but offers a very one sided view, stressing that contact with biological or birth siblings does more harm than good and that social workers all too often force this kind of contact on the fostered child, finding it stressful and sometimes traumatic. Whilst we are sure this does happen, the lack of clarity in this area, and training, means that social workers often get the balance wrong here. Sometimes children do want to see their birth families. Once again, this issue touches on the very confusing way the government goes about producing, and sharing, legislation and policy on child welfare. The solution here is the same as it’s always been – high levels of training for social workers, with an emphasis on really understanding what each child needs. And crucially, ensuring the foster carers don’t consciously, or unconsciously, make a fostered child feel they have to ‘choose’ a family.

There is also a superficial look at the way fostering agencies recruit foster carers. The report suggests that this is often done in an altruistic and noble way, however we know from experience, and our own investigations on social media, that this is not the case. The report does not mention councils’ and agencies’ use of tweets about fostering fees and paid holidays to entice carers.

It’s a long report at over 125 pages, so we’ve decided to add some important quotes from it and add our comments below them. We’d love to hear your thoughts, too:

“In the early 70s, around 29,000 children, 32-35% of all looked after children were in

foster care. This rose to 50% in 1985. The proportion has since increased steadily and

has been stable at around 73% to 75% since 2011.”

The question over why this increase has risen so sharply over the last few years is still unanswered. The President of the Family Division James Munby promised to get to the bottom of this, but he has not been able to do so. The answer lies in the fundamental economic drivers inside the sector, which are at times complicated and irrational, but when looked at from a council’s perspective become much clearer.

“The majority of children in foster care – 60% – are aged 10 or over.”

Babies and very young children are still far more likely to get adopted than older children. It is no surprise then, that the majority of fostered children are over the age of nine.

“The mean duration of the 49,240 foster placements ceasing during 2016-17 was 369

days. 26% of foster care placements that ceased had lasted less than a month, 48%

had lasted between a month and a year; 12% had lasted between one and two years;

and 13% of placements had lasted for more than two years.”

The amount of bouncing around foster children do is unacceptable and needs to be addressed properly. The report recommends focusing on front line customer service in order to make sure placements are well set from the start, but the reality is far more complex.

“In 2016, 25% of children in foster placements reached the new expected standard

or above in the headline measure for reading, writing and mathematics at Key Stage

2 (KS2).”

This is an appalling figure.

“In 2015-16, the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), (a standardised

measure of children’s emotional and behavioural health35) completed for children in

foster care aged 5 to 16 showed 13% had ‘borderline’ scores and 36% had scores that

were a cause for concern.”

This statistic is also terrible.

“The proportion of children with ‘borderline’ and ‘cause for concern’ SDQ scores is significantly higher for children placed with IFAs. In 102 out of 146 local authorities where data was available, average SDQ scores were higher for children placed with independent providers. “

So what were the scores, exactly?

“There were 44,320 approved fostering households as at 31 March 2016, less than a

1% fall from the previous year (44,625).”

“Placement stability is hugely important but stability over many years, stability which might reasonably compare with what we might term normal childhood, is troublingly rare, with too few placements lasting for longer than five years.”

There needs to be an investigation into the kinds of households taking on children, in order to fully understand why placements are breaking down, and what can be done to improve them. As the economy makes it even harder for families to survive, there appears to be an upward trend in families who could also be identified as vulnerable, taking on children in order to bolster their income. This effectively means that an already vulnerable child may be entering a stressed home, which could impact that child’s wellbeing.

“About 67%, (29,720) fostering households were registered with local authorities and

the remaining 14,595 fostering households were registered with IFAs.”

Most of this ‘market’ is dominated by councils, or government bodies. Only 33% of fostering households are registered with independent agencies.

“47% of all IFA long-term households offered permanent or long-term placements in comparison with 38% of local authority households. Three quarters of long-term

households (415 households) that provided multi-dimensional treatment placements as a primary offer were in the IFA sector.”

“Despite the occasional suggestion that IFA care might be poorer, we found no discernible difference in the quality of care offered by local authority and IFA carers.”

This data seems to suggest that independent agencies fare better when it comes to stable placements.

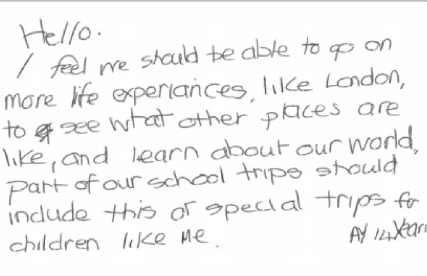

Quote from a thirteen year old in foster care, which needs no comment from us:

“I am of a place in life where things like getting your hair cut or ears pierced are

things that people around me can go and do whenever they feel like it. [But] I have

to ask the local authority before I get this done and sometimes this can be denied, or

my social worker won’t answer to this because they have too many cases. I feel

that children in long-term care shouldn’t always have to consult the council on these

decisions… Long term foster carers know these children better than the local

authority, therefore why should the local authority have more say in a foster child’s

life than their care givers?”

This report does not really tell us anything new. It does though, act as a gateway for the government to continue making the same mistakes over and over again when it comes to children in care. Because whilst it looks at the financial aspects of foster care for carers, agencies and councils, it fails entirely to look at the inherent commercial conflicts of interest involved, which are at the heart of the terrible state of play for kids in foster care.

Reblogged this on tummum's Blog.

LikeLike

As long as thousands of children are taken from parents who may be imperfect but who love them fostering will fail ! As long as contact with parents is supervised and controlled to the extent that laptops and phones are confiscated ,conversation is restricted to banalities and only in the English language and as long as children cannot tell their parents about abuse suffered while in fostercare fostering will fail children.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Reblogged this on World4Justice : NOW! Lobby Forum..

LikeLike

Reblogged this on | truthaholics and commented:

“The question over why this increase has risen so sharply over the last few years is still unanswered. The President of the Family Division James Munby promised to get to the bottom of this, but he has not been able to do so. The answer lies in the fundamental economic drivers inside the sector, which are at times complicated and irrational, but when looked at from a council’s perspective become much clearer.”

LikeLike

This is concerning as children in care need support more than ever as they may be missing there birth family if it was a case of risk of future harm is the reason for removal, or they were pushed into signing a section 20 and no abuse happened. Or if a child was harmed in anyway they need love and support more than ever. If a child is loved by there parents they need to be able to have contact in normal places like soft play for younger children or gaming areas for older ones. If abuse and neglect might of happened contact should be supervised till it can be changed to unsuppervised. Only abused children who don’t want contact should there be none. I lost my babies to forced adoption not because of abuse but because of ill health and struggles with housework. I had no support while my son was in care and made the mistake of becoming dependent on my ex as i was scared and vulnerable as i was facing cancer. My ex was suddenly accused of domestic abuse when there was none. And because of things he did when he was young and stupid he was tarnished as a bad parent. I would never get back woth my ex as j don’t love him but i lost my babies in the end for his issues yet j would of kept him away and only allow supervised contact. Also i hate how someone who only reads paperwork and doesn’t supervise a contact could go into court and judge a family

LikeLiked by 1 person

We remain a society failing to listen to cries from parents needing help rather than condemnation and ostracisation, as well as their children who also need love and understanding.

Our society is too quick to deal out punishment for perceived bad behaviour while being pitifully slow to offer the helping hand that enables victims to climb out of the bog of despair with its endless round of hopes dashed by circumstances.

Of course much depends on the individuals, but few are beyond redemption given the right kind of help given with a good heart. As ever, money, and the lack of it governs what is ultimately on offer.

LikeLike

Pingback: Foster Care Review Confirms The Sector Is Still Failing Children. « Musings of a Penpusher

“The report touches upon contact with siblings and birth parents, but offers a very one sided view, stressing that contact with biological or birth siblings does more harm than good”.

Well Well Well, i wonder why they came to that conclusion.

i would think the reason why Contact with parents and family is being cut off for no good reason while the Govt dont seem to care about it is because its the Govt who have set these guidelines and procedures for LAs to follow when children are placed in care.

it would take some serious heat from protesters and large numbers of the public to make them change the Policy on this disgraceful situation which almost certainly constitutes a violation of Human Rights.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dr M. The entire report is skewed towards making out fostering is the solution to the high numbers of children in care. As a result, one of the ways in which to make this option attractive to potential carers, is to keep birth families out of the equation. I think that’s what this is about.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely, i would say keeping birth families out of the equation is exactly what this is about. it also helps them groom the children for an easier transition to a new home with strangers.

shurly Sir James can see this for what it is so why isnt he getting his teeth into it and making some waves. the Elephant in the room is big enough for all to see.

Unless your Blind!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I has a call yesterday from yet again loving parents who lost 2 children the children were sent to a foster care in Scotland although the parents live in London, so contact is a no go, but this is not a one off, kids are suppose to be fostered close to home, so what is going on with sending kids to Scotland

LikeLiked by 1 person

the SS obviously didnt want the parents seeing the children so placed them as far away as possible.they should go through the 3 stage complaints procedure at their Local Authority then go to the Ombudsman.once that is finished with.

LikeLike

Pingback: Foster Care Review Confirms The Sector Is Still Failing Children. | tummum's Blog

Pingback: Cash Strapped Councils Offering Up To £1,000 To Fill “Difficult” Children’s Services Roles. | Researching Reform

Pingback: Is Government Quietly Privatising The Social Care Sector To Sell It For Parts? | Researching Reform