A research paper published in the Children and Youth Services Review in 2009 is a hidden gem worth reading, not just for its breathtaking insight into how foster care and adoption affects children but also in its call for radical reform of current permanency practices and policies.

![]()

Written by Gina Samuels, at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration, this study worked with 29 young adults who had experienced foster care. The study focuses on ‘ambiguous loss’, a theory which suggests that children who experience a complete disconnect from their birth families become unsure as to what family is, who is a part of their family and creates long-term confusion which cannot be resolved. It is often defined as the most stressful type of loss humans can experience, because unlike the death of a loved one which can be mourned, ambiguous loss blocks a child’s ability to grieve and move on, so they can never gain closure.

The overwhelming sentiment that comes across in this study is that, regardless of family shape, size or style, young people wanted to be in an environment where an enduring physical presence of unconditionally accepting people provided an unbreakable bond – no matter what.

The research findings are powerful, and apply equally to the UK child protection sector, as they do to the US’s child welfare system.

Key highlights include:

- The feeling that foster care does not feel ‘like home’

- Most young people interviewed hoped to be returned to their biological parents, escape foster care or create their own families to better reflect their own sense of permanence

- Most young people in the study said they did not want to be adopted and that all they wanted was reunification in childhood rather than adulthood, so that they could overcome deep feelings of ambiguous loss

- Multiple foster care placements, and constantly ‘moving around’ from home to home aggravated the symptons of ambiguous loss

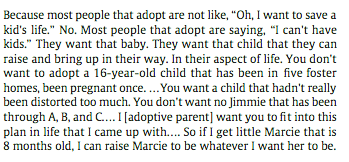

- Some young people interviewed felt that adopters wanted only babies rather than older children in order to mould them into the people they wanted to raise as their own, in their own image, or way of life

- Some young people involved in the study said they recalled their social worker telling them that being older lowered their chances of adoption

- Although some participants had positive foster care experiences, they also hoped to be reunified with their biological parents, whom they viewed to be their ‘real’ parents

- The removal of children from their birth parents into foster care is an institutionally caused ambiguous loss and trauma

- Foster care highlights the ripple effects facing children who can’t be guaranteed access to a parent or extended family member

- Neither the law, biology, of what children saw ‘on paper’ were viewed as trusted pathways to experience the permanence and family identity the participants in this study desired

- A radical shift in current child protection policies and practices is required to incorporate the perspectives highlighted in this study

- The child welfare sector needs to look at more flexible concepts of family as defined by individual family units in order to better support vulnerable children

Whilst this study has its limitations, like all studies, it is hugely important for better understanding why our current permanency placements for children are still not sophisticated enough. If you have a moment, it is very much worth a read.

In other words forced (contested) adoptions and forced fosterings” just ain’t right !”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on World Peace Forum.

LikeLike

This certainly makes very important points – most importantly that the vital human need for biological identity and belonging is disregarded. Isn’t the main issue here that the ideas behind Social Service practice is that families can be ‘created’ – that the biological ‘truth’ of family is considered irrelevant.

LikeLike

Please note:

Flawed and outdated social work policy about Contact.

http://www.communitycare.co.uk/2016/05/13/failure-challenge-independent-social-worker-report-key-error-case-dad-beat-four-year-old-daughter-death/

LikeLike

Reblogged this on No Punishment without Crime or Bereavement without Death!.

LikeLike

SS are playing God, creating social engineering, with children’s lives, whether adoption or fostering. They do not have that right and certainly do not seem to acknowledge that older children in foster care have any rights to express what they want, including those who wish to return to their families when it is possible to do so except for SS dictating otherwise and refusing to be overruled and shown to be in the wrong. The natural course of events is parents making decisions about their children, not sws. Remove that right and the children will feel disregarded. This is real emotional harm.

LikeLike