With the Prime Minister setting out his latest set of measures to deal with counter-extremism this week, it seems as if more and more guidelines are being published, but are they being incorporated into social work practice, and how effective will they be?

Whilst extremism is a broad phenomenon, the Family Court will be concerned mainly with the radicalisation of children and vulnerable adults. In order to prepare the family sector for these types of cases, the President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, released a set of guidelines this month on how he envisages the cases to be processed.

Magazine Community Care is keen to know if the social work sector is ready for these changes, and as such they have prepared a questionnaire to that effect, in which they seek to find out, “how well you understand [radicalisation], how you are dealing with the cases of radicalisation on your caseload, whether your local authority is supporting you and just how confident you feel about your ability to deal with a case where radicalisation is a factor.”

We hope that the family justice system has more than just The President’s Guidance and the Prime Minister’s strategy materials to work from. Ideally, there should be clear signposts to a working definition of radicalisation, and the risk factors within radicalisation, as well as psychology guidance on behaviours related to this phenomenon. In this excellent article written by Durham University Law Lecturer Alan Greene, the government’s definition of extremism (rather than radicalisation) is included. It is:

“The vocal or active opposition to our fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also regard calls for the death of members of our armed forces as extremist.”

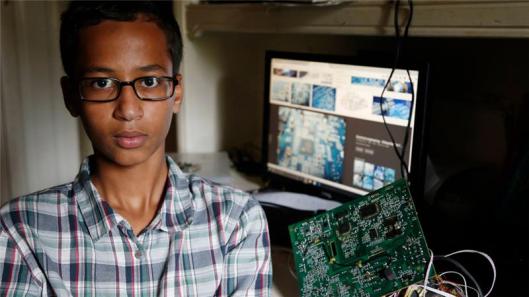

So, what do you think? Is the practice guidance in this area clear and thorough, or can we expect to see children taking homemade clocks into school finding themselves subject to Care Orders?

The case of Ahmed and the clock speaks for its self was it because he is a Muslim child or is this the truth of control of the children, as we are aware children have been the silent witnesses for thousands of years, so another child without a voice. When Cameron lost a child to death I wrote to say how we the families were saddened and that Cameron’s family could now go forward with the memories, at the same time I wrote that to lose a child in death there is a closure but for the thousands of families who lost their kids to the care system there is no closure it is a living hell every day with not knowing if their kids were alive or dead and therefor have to continue to live day in day out for untold years in the hope that their child will find them should they be alive. As for Munby he should practice what he preaches and open the family courts and give the kids a voice, but then Munby is aware that to open the courts and give a kid their rights then the care system will be exposed but we know Munby has to do as he is told to do, other wise jobs will be lost along with the billion pound charities and foster/adoption agencies, And now we have thousands of immigrants arriving so how many more kids will be taken into care, my god I hate to think, but then there is more to the Muslim immigrants arriving to the EU then most people will know, we have already read in the media of how Muslims SUPPOSIDLY are taking control in this so called British Empire, its internal wars and the bloody Brits have done this for years, the helpline has heard from many Muslim families in the UK with Muslims having many children wow so how much more money can be made to steal the Muslim kids by the Governments. There is no way in the WORLD the British kids from what ever religion are they safe just as the little boy and his clock.

LikeLike

.” In order to prepare the family sector for these types of cases, the President of the Family Division, Sir James Munby, released a set of guidelines this month on how he envisages the cases to be processed.”

The one word “processed” here rings a bell. Its the same bell that rang under Hitler regime.

As a species we keep going round and round the hampster wheel and no change happens, which of course is the idea for some.

LikeLike

” Is the practice guidance in this area clear and thorough, or can we expect to see children taking homemade clocks into school finding themselves subjected to Care Orders?”

Many gifted and talented children already are subjected to “care orders” because some see these children as a threat to society. Some adults are also jealous of these children and deliberately cause them trauma in order to try and destroy their gifts. I have witnessed many such cases. Cases where children had inventions and pattens and now these adult children are zombies after the womderful “care” they got from the system.

LikeLike

Ladyportia I agree with you and having spoken to so many from the care system living on the streets Hitler was put into power by ???? and continues to do so by the SS. If I had a wish I would wish for all who work oh sorry get bundles of money “In a child’s best interest” TO BE BANISHED from this earth, as for kids in care who are very talented just as the little boy and his clock they become a nothing

LikeLike

Reblogged this on No Punishment without Crime or Bereavement without Death!.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on World4Justice : NOW! Lobby Forum..

LikeLike

Natasha, many years ago when I was a landlady in London I had over 30 tenants and most were au-pares, and worked for the mega wealthy, many au-pares would work for a few months for a family then leave, and the children they looked after had no stability with many of the au-pares telling me many of the kids they cared for never saw their parents as they were always out at work then out for dinner and other, so how many judges MPs Lords also grew up with no love or stability perhaps this is why they are all a cold blooded unloving uncaring heaps of ???? and so for them it is send the kids to care the parents cannot affords au-pares,

LikeLike

I think that kind of parenting has a lot to answer for.

LikeLike

Yes Maggie.

Why do you think patriarchy saw a chance to use women and mothers for cheap labour during and after the war?

Hitler and his best interests of the child learned in experiments to cut out the mother love and in one generation love and care is gone and the next generation have no idea how to care for their children as they have not experienced it and do not know what it feels like.

Today we see this war on mothers daily in courts.

Of course women and mothers were told they were then equal to men- but they were and are still doing the 24/7 job of looking after their children as well as working the same hours as men- and the child care is worth nothing ?????unless an au pair or nanny is doing the caring.

Why would fe-males want to become like males and be 50% of who they really are?

Then we learn about young children at boarding schools and how it imprinted them- abandonment, cold, sterile, rigid, military style pseudo parenting.Rape, mental torture, physical torture etc, etc

Most of those who went to these so called prestigious schools are devoid of feelings of love and belong to a cult- as explained here.

They are mere puppets who dance to the tune of their masters.They cannot think for themselves. They cannot feel and so cannot care for themselves or any other human being.

http://www.whatonearthishappening.com/news/542-watch-mark-s-presentation-the-cult-of-ultimate-evil-order-followers-the-destruction-of-the-sacred-feminine

LikeLike

With all of my research and with info from people in high places to include ex CID officers the truth is there for all to know that paedophiles at the top is rife Munby and the rest of them in Governments are aware but it all comes back to the saying

THAT MONEY TALKS, AND IT IS NOT WHAT YOU KNOW BUT WHO.

So the paedophiles and abusers of kids in care will have as they have had for 100s of years a complete cover up, and the minuet a paedophile in governments name pops up then in comes the media and names a top celebs as a paedophile and the governments paedos name is gone. My latest research is why are some Universities supporting and paying for kids from foster care to go to University, well just look at Cambridge University who supports and pays for kids from care and on the news of yesterday another paedophile at Cambridge National health was charged with child sex offences, people really need to look into Cambridge Universities because they have many Psychiatry’s employed along with performing many experiments. WHAT ON THE FOSTER KIDS ??????? and the fact that people will say Oh how wonderful to support foster kids, don’t you believe it, WHEN WORLD WAR 2 CAME TO AN END THERE WERE NO MORE GUINIE PIGS FOR EXPERIMENTING ON SO IN CAME THE NATIONAL HEALTH PRISONERS ELDERLY KIDS IN CARE AND THE WHOLE BLOODY NATION AS THE GUINNIE PIGS.

University Academics Say Pedophilia Is – Truth Uncensored

truthuncensored.net/university-academics-say-pedophilia-is-natural-for-… Cached

27 Jun 2015 – An academic conference held at the University of Cambridge said that pedophilia interest is “natural and normal for males”, and that “at least a …

Why is Cambridge hosting academics who say paedophilia …

thetab.com/…/top-unis-slammed-as-sanctuaries-for-paedo-apologists-173… Cached

9 Jul 2014 – Top unis are under fire for hosting paedophile apologists who claim … A speaker at a Cambridge University conference said most men are …

http://search.cam.ac.uk/web?query=foster%20children%20and%20psychiatry

© 2013 University of Cambridge, Department of Psychiatry/Cambridgeshire Film Consortium. All rights reserved.

(a collaboration between the University of Cambridge and the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with a wide range of Cambridgeshire and East Anglian Health and Service Providers).

LikeLike

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2315185/Five-year-olds-Germany-given-sex-education-book-achieve-orgasms-condom.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2315030/Teachers-lessons-pornography-tell-pupils-bad-experts-say.html

LikeLike

Most parents have no idea what is being taught to their children in schools as books are not always brought home.

The ultimate aim is to destroy the caring feminine- like the Jesuits- make sure boys never learn the love of a woman.Its all about Sex and sex is not necessarily love making as we all know.

When we have a city that over 60% of male youths claim to be gay- because of peer pressure – but yet go around in gangs gang raping girls- especially from the care system- then somehing is seriously wrong.

LikeLike

Dr Judith Reisman is a delight to read up on. She was and is light years ahead on this pro child rape agenda – aka pedophilia.

Grooming and Hypersexualising children is the agenda and it suits child rapists.

http://www.wnd.com/2011/08/336741/

http://www.drjudithreisman.com/archives/2014/03/the_kinsey_cult.html

THE KINSEY CULT: How they’re hypersexualizing your kids

Exclusive: Judith Reisman explains history of teachers’ ‘attitude restructuring’

If we study the Roman church we learn where this pro child rape rite/right came from and who the mols were and are.

http://one-evil.org/content/acts_child_molestation.html

“The modern clinical term Pedophilia

The term Pedophilia (first recorded in 1951) is a modern term created from the Greek words (gen. paidos) “child” (see pedo-) + philos “loving.”

Contrary to public belief, the term Pedophilia has the unfortunate literal meaning of “loving children”, than the criminal action of child abuse. While Pedophilia has absolutely no religious significance as a word, its continued use as a term to describe child molestation and child abuse is misleading—implying those branded as “pedophiles” have some emotional empathy towards their victims (implied by philes/philos-love).”

These cults expect everyone to fall into line and allow child rape and accept it as normal.

However for anyone with knowledge – child sexual abuse is soul murder.

This judge noticed the DEAD EYES and could not explain the murder of the soul.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/10/23/how-society-silences-sexually-abused-children/

“On some days, I had to look at 50 images, and on others, I viewed 300. Occasionally there was video, which I came to dread the most. Not only were the children silent, but also, in both the photos and video, their eyes were dead. I don’t know if that’s a result of survival, accommodation or fear. Maybe it’s all of those things.”

Also the question as to why children do not scream out for help- when in truth the precident is already there re rape victims freezing and no sound comes out. They turn to stone.

So when child rapists say children enjoyed the rape and never uttered a word against it – this is why.!!!

“The precedent, for the first time in the ACT, allowed an expert to tell a jury it is not uncommon for rape victims to ”freeze” during an attack.”

http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/fright-freeze-precedent-will-change-consent-in-act-rape-trials-20140406-3673r.html

LikeLike

I will reply in greater details later as I have an appointment shortly but my god you are so correct, I named the charity children screaming to be heard because that is exactly what they are and have been from dot,

LikeLike

I do agree with what you say even for the kids who are raped so many times and have no tears what is the point as I have been told by many kids from care they say because there are or were no doors to open for them which comes back to children screaming to be heard, I think with the knowledge Lady Porta has and my little bit its a shame we cannot do any thing to help the abused kids the only thing we can do for them is to CRY.

LikeLike

Pingback: Are You Ready For Radicalisation? | National IRO Manager Partnership